Trade & Fragmentation: The End of Globalisation as We Knew It.

How firms and countries are adapting – near-shoring, regionalisation & supply-chain transformation.

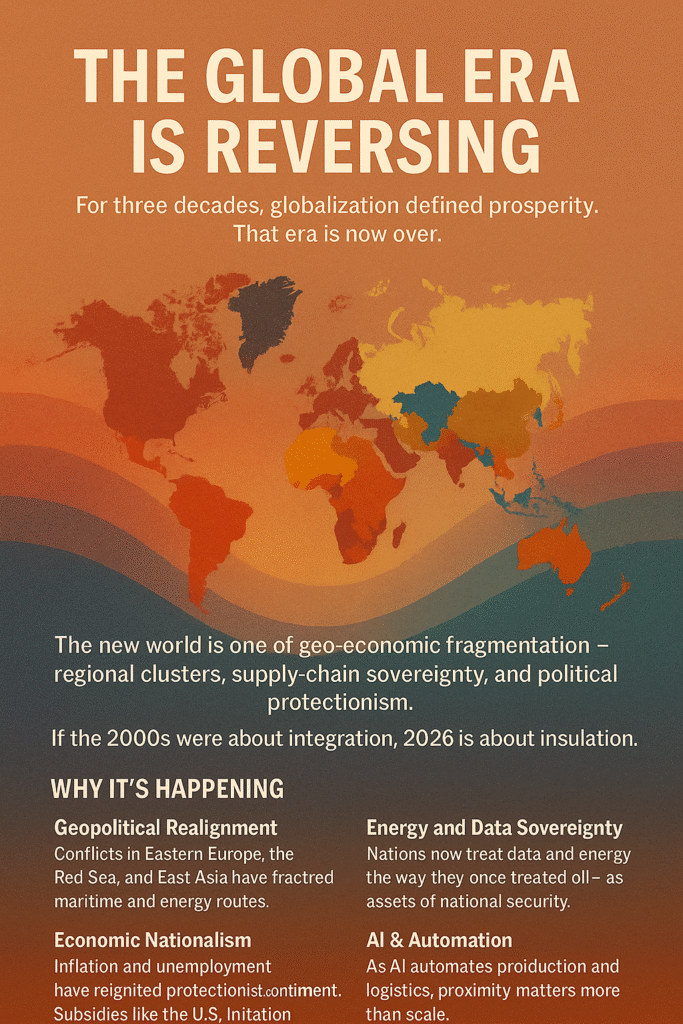

Globalisation as we knew it” may indeed be over, a sentiment echoed by figures like HSBC chair Mark Tucker. The current landscape is characterized by “geo-economic fragmentation,” a policy-driven reversal of global integration, leading firms and countries to adapt through strategies such as near-shoring, regionalization, and comprehensive supply-chain transformation.

For decades, the paradigm of globalisation—vast international trade flows, deep cross-border value chains, and production networks spanning continents—served as the engine of growth for many economies.

But today, the landscape is shifting. Rising trade barriers, geopolitical tensions, supply-chain disruptions (for example from the COVID‑19 pandemic), and a push for greater resilience are converging to produce what many analysts call trade fragmentation. This isn’t just a temporary hiccup—it signals a fundamental re-ordering of how countries and firms engage in global commerce.

As the World Trade Organization (WTO) frames it, we are witnessing “re-orientation and fragmentation of global trade” rather than a simple return to the old normal. The question is no longer whether globalisation is dead, but how it is being re-shaped, and how firms and countries—especially in India and elsewhere in the Global South—are adapting to this new regime.

In this article, we will:

Define what trade fragmentation means and why it matters.

Examine key drivers: trade barriers, geopolitics, supply-chain disruptions.

Discuss how firms and countries are responding—near-shoring, regionalisation, supply-chain diversification.

Highlight implications for Indian firms and policymakers, and for global firms with India supply-chain footprints.

Offer strategic recommendations for adapting to the new world of “fragmented globalisation”.

What is trade fragmentation, and why is it important?

Trade fragmentation refers to the increasing segmentation and decoupling of global trade and value chains—where flows of goods, services, investment and technology become more aligned with geopolitical, regional or national boundaries rather than purely efficiency-driven global networks.

Key facts:

A recent study finds that trade flows have become significantly more sensitive to geopolitical distance (the extent of political alignment or distance between trading partners).

The WTO’s working paper shows that since the war in Ukraine, trade between hypothetical “East” and “West” blocs has grown about 4 % slower than intra-bloc trade.

According to the International Monetary Fund (IMF), global trade restrictions and fragmentation could reduce global output by up to 7 % or about US $7.4 trillion in today’s dollars.

The European Commission warns that a more fragmented world trade system—driven by decoupling, supply-chain re-balancing and increased trade-policy uncertainty—could impose significant long-term costs, particularly on low‐income countries.

Why this matters:

Firms that rely on global value-chains (GVCs) face higher risks: more tariffs, more regulatory complexity, more supply-chain disruption, more cost inflation.

Countries dependent on export-oriented manufacturing or deep integration into global supply chains may find their competitive advantage eroding.

Emerging markets risk being “left out” if investment and trade are re-oriented towards closer or more politically aligned markets.

The concept of globalisation driven purely by cost and efficiency is being replaced by an integration model driven also by resilience, security, sustainability and geopolitics.

In short: we are not simply back-tracking to the 1990s trade regime; we are entering a new era of fragmented globalisation.

What’s driving this shift?

1. Rising trade barriers & protectionism

In recent years, many countries have introduced trade-restrictive measures. For instance:

The number of new trade-restrictive measures introduced globally has increased dramatically.

The WTO cautions that splitting the global trade system into separate blocs could reduce real income globally by about 5 %.

Trade in goods between countries with greater geopolitical distance has become increasingly weak.

2. Geopolitics, technology and “friend-shoring”

Geopolitical competition—especially between major powers—means countries increasingly prioritise trade and investment with “friendly” or aligned states rather than open global networks.

Technology restrictions, export controls and national-security considerations (for semiconductors, critical raw materials, etc) mean that supply-chains are being structured by strategic rather than purely economic considerations.

The term friend-shoring or ally-shoring has emerged: shifting supply chains to politically aligned countries to reduce strategic risk.

3. Supply-chain shock, resilience and near-shoring

The COVID-19 pandemic exposed vulnerabilities in global supply-chains (just-in-time, single-supplier dependencies, long logistics chains).

Firms and governments are asking: “How do we make supply-chains more resilient?” The answer often: shorten them, diversify them, bring them closer (near-shoring), regionalise them.

But research shows that so far, despite these impulses, there is no strong evidence that near-shoring has overwhelmingly resulted in a major global shift to regional manufacturing. According to the WTO: “no evidence of an increased regionalisation of world trade since the pandemic or war in Ukraine.”

4. Shift in global value-chain logic: from pure efficiency to resilience & security

As one study puts it: “The logic of unrestricted globalization is being replaced with more fragmented trade and economic relations.”

Instead of only minimising cost, firms and countries are embedding redundancy, diversification, proximity, and political alignment into their supply-chain and trade decisions.

For many low-income and emerging economies this means they may lose out if they were plugged into “open global” chains that are now being re-organised in favour of regional or allied-centric networks.

How firms and countries are adapting

With global trade patterns shifting, we see several strategies being adopted. I’ll highlight them, and then look at implications for India and Indian firms.

A. Near-shoring and friend-shoring

Near-shoring: relocating manufacturing or sourcing closer to home, regionally or domestically, to reduce logistics risk, shorten lead times, mitigate trade-barrier exposure, and enhance responsiveness.

Friend-shoring: relocating or diversifying supply-chains towards countries with close political or strategic alignment (for example: US firms sourcing from Canada/Mexico rather than China).

Example: The US and other advanced economies are encouraging supply-chain shifts to countries such as India and Mexico.

B. Regionalisation of value-chains

Rather than global manufacturing networks spanning multiple continents, companies are increasingly building regional ecosystems: Asia-Pacific, ASEAN, South Asia, Africa, Europe.

Advantages: shorter supply-chains, closer to markets, quicker response, alignment to regional trade agreements and standards.

However: As flagged by the WTO, the “increased regionalisation” is not yet heavily evident globally.

C. Diversification & multi-sourcing

Firms are no longer comfortable with “single-source” supply chains in one country or region—they are adopting multiple sourcing strategies across countries to reduce risk of disruption, blockade or sanction.

This sometimes means cost trade-offs—less absolute efficiency, but more resilience.

For example, critical raw-material sourcing is shifting away from heavy concentration in one country.

D. Re-shoring / on-shoring / domestic production expansion

Some firms are choosing to bring production back home (to reduce exposure, protect IP, satisfy local-content/sovereignty demands, shorten delivery times).

Especially in sectors deemed strategic: semiconductors, defence, critical minerals, batteries.

E. Country / policy responses: building “value-chain sovereignty”

Countries recognise that deep dependence on one partner increases vulnerability (to sanctions, trade wars, pandemics, logistics shocks).

So governments are emphasising policies like “supply-chain resilience”, strategic autonomy, diversification of trading partners, incentives for domestic capability in strategic sectors.

Example: The WTO’s Director-General recently emphasised that rather than abandoning global trade, the trading system must evolve (termed “re-globalisation”).

Implications — with a special focus on India and global firms with Indian links

For Indian firms & policymakers

India is in a strong strategic position. As many global firms seek alternatives or complements to China-centred supply-chains, India offers: large labour pool, rising manufacturing ambition, improved infrastructure, favourable government initiatives (e.g., “Make in India”).

But risks remain: India must ensure ease of doing business, logistics/port efficiency, continuous skill development, quality of infrastructure, regulatory stability. The cost advantage may erode if these fundamentals don’t keep pace.

For Indian exporters, as trade fragmentation advances, closer regional integration (South Asia, ASEAN, MENA) may become as important as global reach. India should double down on regional value-chains, trade agreements, connectivity.

Policymakers need to grid for the new mindset: not just efficiency-first but resilience, strategic diversification, supply-chain sovereignty. India can position itself as a “friend-shoring” destination for major economies.

At the same time, India must manage risk of being bypassed if global value-chains re-organise into blocs excluding India. Ensuring continuous alignment with multiple partners will be key.

For global firms with Indian supply-chain footprints

Firms sourcing or manufacturing in India should view the country not only as cost/scale advantage but also as part of their resilience playbook: hedge against over-concentration in one country (e.g., China).

They should evaluate the entire supply-chain footprint—including logistics, trade-barrier exposure, regional demand, geopolitical risks—and determine whether India (and the broader South-Asia region) offers viable “near-shore” or “alternative-shore” opportunities.

Firms should consider regional hubs: India could serve South Asia / Middle East / Africa market flows, reducing lead times relative to distant chain links.

Supply-chain reconfiguration will require investment in infrastructure, skills, standardisation, compliance. The lead-time for this matters. Early movers may gain first-mover advantage in India.

Firms must monitor trade policy changes: Tariffs, non-tariff barriers, export controls, local content rules may increase globally. Supply-chains anchored in India should build flexibility to respond.

Challenges & caveats:

Fragmentation is costly. The shift from purely cost-driven global networks to resilience-driven ones often means higher unit costs, duplication, less scale-efficiency. The IMF warns of output losses.

Even though near-shoring and regionalisation are gaining attention, evidence suggests they haven’t yet created a sweeping global realignment: the trend is gradual and uneven.

Emerging markets face risk of being squeezed. Countries heavily dependent on trade with geopolitical rivals may find their options narrowing.

Simply moving production to a new country like India is not sufficient: supply-chain ecosystem, infrastructure, trade-agreements, regulatory clarity, labour skills all matter—and often take years to build.

There remains a risk of eroding global cooperation: if trade becomes dominated by blocs and friend-shoring, the benefits of open global markets—technology diffusion, scale, innovation spill-overs—may be reduced. This could slow global growth.

Strategic recommendations for companies & policymakers:

For companies:

1. Map supply-chain risks: Assess where your production/sourcing is concentrated, evaluate exposure to tariffs, sanctions, logistics disruptions, single-supplier risk.

2. Build a “resilience” layer: Maintain alternate suppliers, diversify geographies, consider near-shoring/region-shoring options.

3. Consider India as part of the strategy: Given India’s large domestic market, improving manufacturing ecosystem, government push, and geopolitically favourable status for many global firms, India can be more than a cost centre—it can be a strategic hub.

4. Invest in agility: Shorter lead-times, flexible manufacturing, digital supply-chain tools, inventory buffers—all help in a fragmented world.

5. Monitor policy/trade-risk signals: Stay alert to tariff changes, export-controls, regional trade-bloc formation, technology-decoupling risks.

For policymakers (India & other emerging markets):

1. Strengthen manufacturing ecosystems: Infrastructure, logistics (ports, roads, rail, air-cargo), reliable power, skill development—these are prerequisites to attract firms re-shoring/near-shoring.

2. Pursue trade and investment agreements: To become an attractive hub, integrate regionally (South Asia, Middle East, Africa) and globally (free-trade agreements, investment treaties) to reduce non-tariff barriers and increase predictability.

3. Promote supply-chain resilience as a policy theme: Craft policies that combine cost-competitiveness with strategic diversification (e.g., support for manufacturing of critical or strategic goods) and promote “India-plus-one” strategies.

4. Leverage domestic market scale: India’s large domestic demand means firms locating in India can serve domestic, regional and global markets—offering a compelling value-proposition.

5. Balance global openness with strategic autonomy: As trade networks fragment, it is tempting to adopt high protectionism. However the cost of isolation may be high. Policymakers need to strike the right balance: openness to global investment and trade, while building resilience and strategic capability.

Conclusion:

The era of globalisation as we knew it—with virtually frictionless cross-border supply-chains, production anywhere, sourcing from the cheapest country, and minimal concern for non-economic risk—is ending. In its place is a new world of fragmented globalisation—characterised by trade blocs, regional supply-chains, near-shoring, friend-shoring, and resilience-driven strategies.

For firms and countries, the imperative is clear: adapt or risk being left behind. Adaptation means re-thinking sourcing and manufacturing footprints, integrating the values of resilience, geopolitics, and sustainability into strategy—not just cost. For India, the present moment offers a window of opportunity: to become a core player in the re-arranged network of global trade and value-chains.

Yet this transition will not be seamless or easy. The costs of fragmentation are real. The benefits of the old model were real. So the challenge is to harness the best of the new order—diversification, regional strength, resilience—while mitigating the risks of higher costs, slower growth and exclusion.

The future of trade isn’t simply globalisation or de-globalisation—it is a re-globalisation: a recalibrated globalisation that recognises the realities of geopolitics, supply-chain fragility and strategic autonomy. For firms and policymakers who recognise this shift and act on it, the future holds promise. For those who remain wedded to the past, the risk becomes increasing marginalisation.

Team- Credit Money Finance

Follow us on LinkedIn:

https://www.linkedin.com/company/intellexcfo-com/

https://www.linkedin.com/company/intellexconsulting

www.StartupStreets.com, www.GrowMoreLoans.com, www.GrowMoreFranchisees.com, www.intellexCFO.com, www.CreditMoneyFinance.com, www.StartupIndia.Club, www.EconomicLawsPractice.com